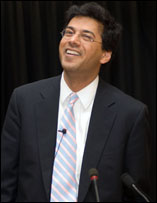

Two weeks ago some of my closest friends from college were in New York for our annual gathering, a tradition we began nine years earlier. The amazing thing about my friends is that they’re game for almost anything, which is how we found ourselves on a beautiful Saturday morning inside a massive auditorium listening to a lecture entitled “How to Live When You Have to Die” by the physician and author Atul Gawande.

Atul Gawande is the new American “Dr. Death.” I mean that in the most optimistic of ways. While Jack Kevorkian made headlines for championing a terminal patient’s right to die via physician-assisted suicide, Gawande is “instinctively against” Oregon and Washington’s assisted suicide laws, which he fears may lead to a mistrust of doctors. Gawande’s focus is on exploring end-of-life care, including ways in which terminally ill and their families come to grips with death .

He opened the lecture by talking about the phone call he received from his wife’s cousin, whose 12-year-old daughter had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a disease that is 85% treatable. Unfortunately, the treatments weren’t working for this little girl, who was emaciated and so ill that she hadn’t been able to see friends for over a year. The cousin wanted to know if they should try the last recourse of treatment — a bone marrow transplant that had a slim margin of success.

Atul Gawande found himself “utterly useless” in this conversation. Years of medical training had taught him to say that there’s always something more we can do. But how to weigh one more radical treatment against the suffering of a loved one?

That question lead him on a journey. If you get the chance you should read his latest piece in the New Yorker: “Letting Go: What should medicine do when it can’t save your life?”

The real take-away from Gawande’s latest work is this — patients benefit most by having someone to talk to about death. In his article he states that “… people who had substantive discussions with their doctor about their end-of-life preferences were far more likely to die at peace and in control of their situation, and to spare their family anguish.”

Above all, there are 4 simple questions to talk through with those who are ill:

1) What do you understand to be your prognosis?

2) What fears do you have about what’s to come?

3) What are your goals as time grows shorter?

4) How much suffering are you willing to go through for the possible trade-off of added time?

One person he talked to said her ailing father thought through these questions and concluded that he’d still want to live if he could eat ice cream and watch football on TV. It was the benchmark she used in deciding upon all medical interventions until the day his condition no longer allowed for these simple pleasures. Gawande reports that a conversation based on these four questions with his own father was “incredibly hard but completely transformational.”

Of course, the premise of the Year to Live class I’ve been taking is that it’s never too early to have these conversations about death with ourselves and with our loved ones. Some day we won’t get life’s winning lottery ticket, as Gawande would say. And having thought about death would hopefully have meant that we used the time we had being as committed to life as possible.

So what happened to the 12-year-old daughter in Gawande’s family?

Her family took her home from the hospital and stopped all but palliative treatments. Ten days later he got the email sent to close relatives and friends saying that she had passed away.

“All is well,” the message read. “Our home is full of peace.”

wow, powerful stories! Something about the “eat ice cream and watch football on TV” bit that gives me goosebumps — in a positive way. Perhaps because the way I finally came to an understanding of the meaning of my relationship to my own father was when I realized talking to him about soccer translated directly into “I love you, I love you, I love you.”

So often the most meaningful messages from the universe manifest in the smallest, seemingly insignificant things, and we walk right by them every day.

thank you so much for this blog and the link .. there is so much that we can look at but to have your words in your year long contemplation on dying.. to guide, is incredibly helpful. i am thinking a great deal these days about creating an environment of peace and dignity based on people’s wishes,, and includes the fear of and direct discussion of dying so our lives are enriched by facing all of our destinies.. xxxx let’s have tea soon.