Years ago, 20 students at The Princeton Theological Seminary were given a copy of the parable of the Good Samaritan and were told they must deliver a sermon about it.

(Quick refresher: A Jewish traveler is beaten, robbed and left for dead by the side of the road. Two religious men pass by without helping. Then a Samaritan — belonging to group that was in conflict with the Jews — stops to help and even pays for the man’s recovery.)

A control group of students was also told they would deliver a sermon, but their topics were other passages from the Bible. Some of the total group of 40 were led to believe that they had only a few minutes before they were to speak; others thought they had more time.

The researchers then orchestrated a situation in which the students had to walk outside to another building to deliver their remarks, passing by someone on the door step who was moaning in pain.

What happened?

Sixty percent of the seminarians walked on without offering help. A seminarian thinking about the parable was no more likely to stop than one given a less lofty topic, and on several occasions a seminarian going to talk on the Good Samaritan literally stepped over the man. Only 10 percent of those who were told to rush to the test site offered help, while 63 percent of those who thought they had a few minutes to spare offered aid. In examining psychological tests given to their subjects, [researchers] found no personality characteristics that predicted helping behavior; the only factor that seemed to predict helping behavior was degree of hurry. (Source)

I have to tell you, I got pretty down when I heard about this study, which was conducted in 1970. If we could walk right by people in pain in the pre-cell phone/BlackBerry/iPod hurry, hurry, hurry days, what would we do now?

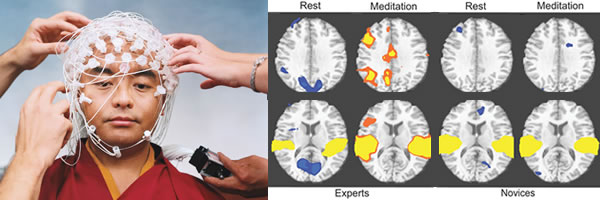

Well, a week ago I had a chance to hear Daniel Goleman, the author of Emotional Intelligence, speak about meditation and neuroplasticity — the ability of the brain to change its structure and function in response to experiences.

Goleman says that we don’t have to be stuck running the same neural connections for the rest of our lives just because that’s what we’ve always done. It turns out that we can become better people by reprogramming ourselves — even when time crunch and life pressures have conditioned us to sometimes turn a blind eye.

And how to do that?

Well-documented study after study, he said, shows that meditators (even people who have meditated as little as 10 minutes a day for 8 weeks) can literally transform their brains by taming their minds. The great news for all of us is that the part of the brain that shows the most activity through meditation is the region that monitors our emotions and generates positive feelings such as happiness. No wonder the Dalai Lama giggles all the time.

Well-documented study after study, he said, shows that meditators (even people who have meditated as little as 10 minutes a day for 8 weeks) can literally transform their brains by taming their minds. The great news for all of us is that the part of the brain that shows the most activity through meditation is the region that monitors our emotions and generates positive feelings such as happiness. No wonder the Dalai Lama giggles all the time.

It also seems that the more time you’ve spent in meditation, the more likely these changes to the brain will be dramatic and enduring.

Simple “mindfulness meditation” will do just fine for decreasing anxiety and stress, boosting your immune system and helping reverse heart disease. And meditation in compassion, in which the meditator focuses on unlimited compassion and loving kindness toward all living beings, seems to be particularly effective at lighting up the part of the brain associated with positive and altruistic feelings.

So the take-away is that being a good Samaritan doesn’t happen through sermonizing, philosophizing, reading, talking or writing about kindness but through consistently working with your mind. To prevent bullying, aggression and violence, researchers are teaching compassion meditation to young people nearing adolescence. Relationships throughout the life-span could clearly benefit from this as well.

I’m willing to bet there are many ways to achieve this same effect, from different religious traditions. If you’ll allow me, here’s a thoroughly unscientific anecdote: my mom sits quietly in a chair by the window for nearly an hour a day with a “prayer chain” — a list of people who could use some form of assistance in their lives — offering up prayers for each one of them. She also spends enormous amounts of her free time helping others and volunteering in the Alzheimer’s ward at the local nursing home. To her, the prayer and the action are inextricably linked.)

All of this brings to mind a beautiful saying by Shantideva, the 8th-century Indian scholar, on how to find happiness in our lives.

Whatever joy there is in this world

All comes from desiring others to be happy,

And whatever suffering there is in this world

All comes from desiring myself to be happy.

Learn more:

Sitting Quietly, Do Something New York Times, Daniel Goleman

How Thinking Can Change the Brain Wall Street Journal, Sharon Begley

Compassion Meditation Changes the Brain, Science Daily

Try this at home:

Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn, an emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School who has pioneered work in the health benefits of meditation, speaks at Google about mindfulness meditation. Meditation instruction starts at about 23 minutes in:

Mindfulness meditation instructions

Sit in a comfortable position that embodies dignity, eyes closed, preferably with the back upright and unsupported. Relax and take note of body sensations, sounds and moods. Notice them without judgment. Let the mind settle into the rhythm of breathing. If it wanders (and it will), gently redirect attention to the breath. Stay with it for at least 10 minutes.

Meditation in Compassion (sometimes also called “Metta” or “Loving-Kindness” Meditation)

Click here for instructions

Facets of Metta, Sharon Salzberg

There’s a great webinar on this topic TODAY by Dr. Richard Davidson Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

http://www.contemplativemind.org/programs/academic/events.html#davidson

And an article called “Your Brain on Meditation,” by Kelly McGonigal in the June 2010 issue of Yoga Journal: http://www.yogajournal.com/health/2601

It’s an interesting issue I grapple with personally. One of the biggest problems is that we’ve all become desensitized to a degree, but the thing is that sometimes it’s necessary. For example, just on my street in SF there are literally dozens of homeless and transient folks, some of them are in really bad shape. Sometimes people will just be sprawled out on the sidewalk and you don’t even know if they’re sleeping or dead. It breaks my heart every time but I simply don’t have the time or mental capacity to check into everyone’s situation. So the question arises, WHEN do we stop to check in with another human being? It’s impossible to help or even give a smile to everyone who is suffering in this world, but the key is to not use that as an excuse to NEVER stop and help. So…I try to stop and show empathy and kindness whenever I can, sometimes randomly, just because, but I don’t beat myself up anymore every time I’ve had to walk by a suffering soul. There are lessons to be learned in either case, but I think it’s important to at least be aware of your surroundings and your own reactions to it and not become numb, even if you don’t always act on it.

Your post should be required reading by everyone, whether they like it or not.

This is an important point, Sven. Easy to point fingers at theology students on the beautiful and protected Princeton campus for stepping right over someone in need, which would have been a rarity.

But how do we handle dozens of cases of suffering we see in the course of every day in a major city? I’m also struggling with this. I’m also trying to teach the kids how to handle it, and how to know the difference between someone who is seriously off balance and someone who they could say hello to. If anyone has any suggestions, I’d gladly take them!